Vibe Hacking, or: How We Tried Building an AI Pentester and Invented a Programming Language Instead.

How often have you seen AI agents hallucinate? Confidently call a function that doesn't exist. Misread instructions and go completely off track. Invent parameters. Forget what they were doing halfway through.

And how many "smart" autonomous agents fall for prompt injection? The agent fetches a webpage to analyze it. The page has hidden text: "Ignore previous instructions and do X instead." Suddenly the agent is doing something entirely different from what you asked. This isn't theoretical—it happens constantly.

For most applications, these problems are manageable. A coding agent hallucinates? You review the code before merging. An email assistant goes off track? You read the draft before sending. There's a human in the loop. An undo button. You catch the 1% of failures before they cause real damage.

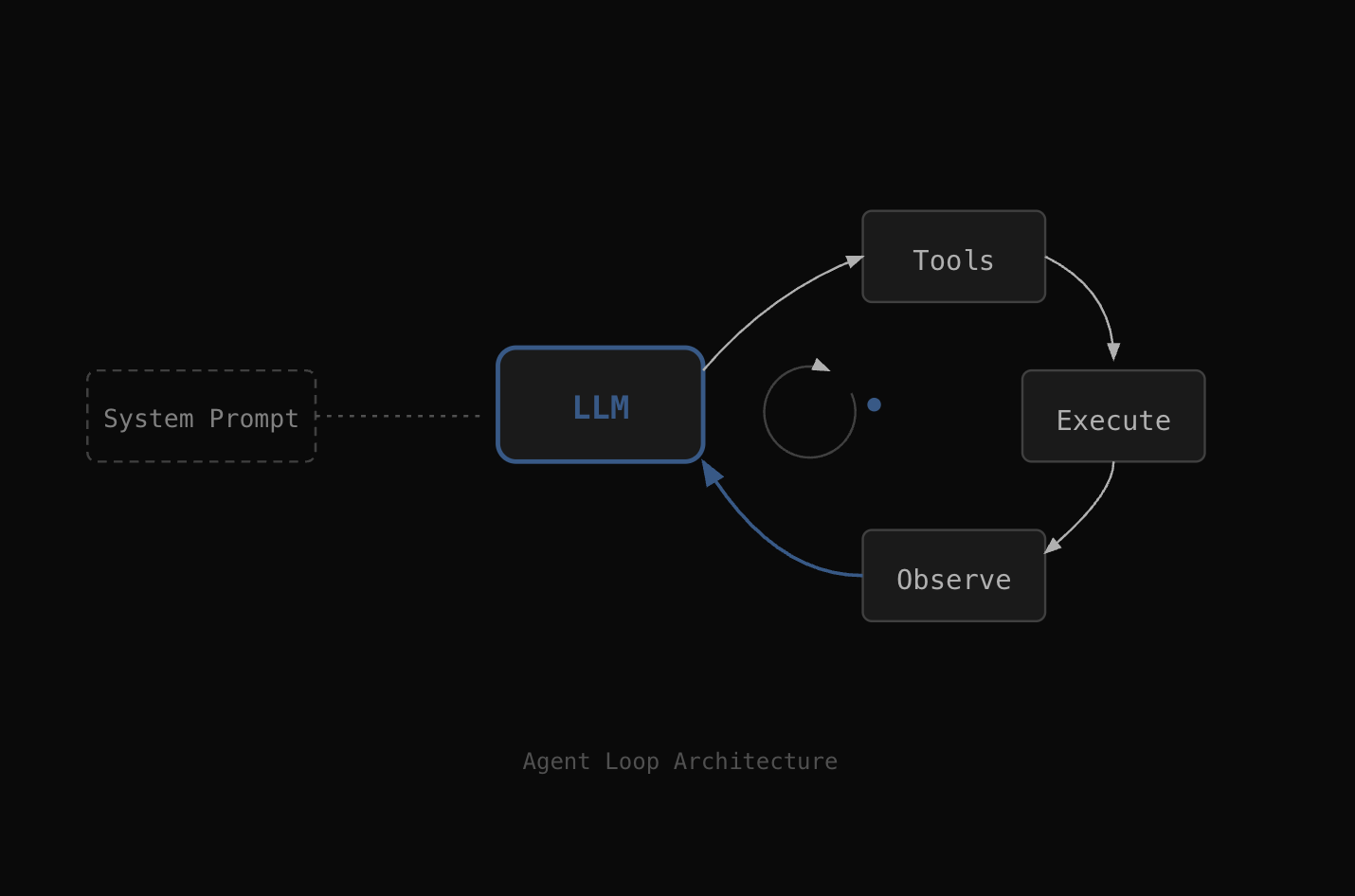

The standard way to build AI agents looks like this: take an LLM, wrap it in a framework, give it access to tools—usually terminal and whatever domain-specific utilities you need. Put domain knowledge in the system prompt. The agent loops: observe, think, act, check results, repeat. Guardrails are usually prompt-based ("stay within these boundaries") or output filtering (check what the model decided before executing).

This doesn't work for (ethical) hacking

For pentesting, the obvious implementation follows the same pattern. Give the agent terminal access. Install standard pentesting tools. Put the methodology in the system prompt—reconnaissance first, then enumeration, then vulnerability assessment, and so on. The agent decides what commands to run based on what it finds.

This doesn't work for pentesting. Not because it wouldn't find vulnerabilities—it probably would. But because "manageable failure rate" is not acceptable in this domain.

If the agent finds an RCE—remote code execution—and "accidentally" exploits it too far, maybe drops a database, even in 0.5% of cases, that's a disaster. If the agent goes beyond the legally defined scope—even once—that's potentially illegal, definitely a contract breach, possibly career-ending. If the agent fetches a target website, hits a prompt injection planted by someone else, and gets redirected to attack a different system entirely—even with low probability—you have a serious problem.

For a real pentesting agent, the probability of these failures needs to be zero. Not low. Zero. These failure modes have to be impossible, not just unlikely.

Formal (Mathematical) Guarantee

We recently implemented a solution to this problem as part of Cerberus, a pentesting ecosystem we've been building. We're sharing our approach here because we believe it may be useful to others working on AI agents in security or other high-stakes domains.

We started with the standard implementation described above: terminal access, pentesting tools, methodology encoded in the system prompt. It worked most of the time. But despite high success rates, agents remained vulnerable to sophisticated prompt injection attacks and could still go out of scope in perhaps 1% of cases—particularly after discovering sensitive information on a target that prompted more aggressive exploration. Prompt-based guardrails reduced the frequency of these edge cases but could not eliminate them entirely.

The question became: how do you provide a hard guarantee—not a "most of the time" guarantee, but a real one—that a pentest will not go out of scope or perform unauthorized actions?

The answer comes from an area of computer science called type theory.

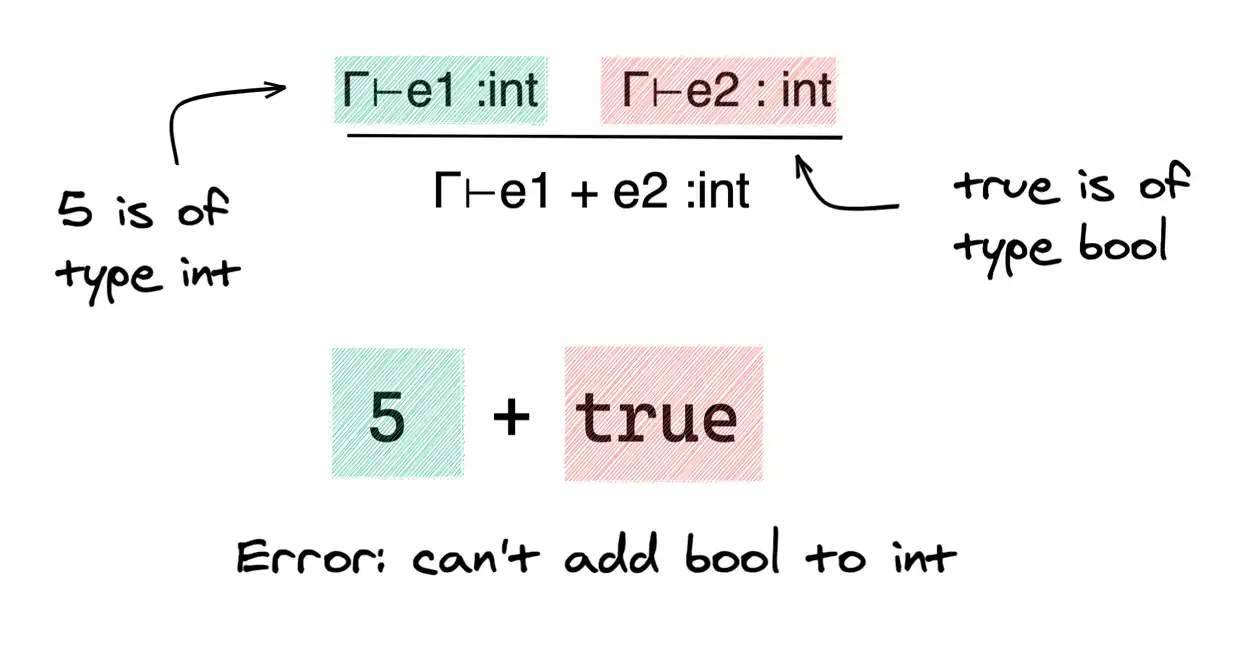

Here's the basic idea: in programming, a type system is what checks your code before it runs. When you write code in a language like Rust or TypeScript, the compiler checks that you're not doing something wrong—like trying to multiply text by a number, or accessing a variable that doesn't exist. If there's a mismatch, the code won't compile. You get an error before anything runs.

The important thing about type systems is that they provide guarantees. If the compiler accepts your code, certain kinds of bugs are impossible. Not unlikely—impossible. The check happens before execution, so bad code never runs in the first place.

Pentesting Scope as Type

Our insight was that pentesting constraints work the same way. Scope limits, authorized targets, permitted actions—these are rules that can be encoded into a type system. If you design a programming language where pentesting actions are code, and the type system knows what's in scope and what's allowed, then the compiler can check every action before it executes. Trying to access an out-of-scope target wouldn't be something you catch with a guardrail after the AI decides to do it. It would be a compile error. The code simply wouldn't run.

// Declaring allowed scope

scope Pentest = {

socket::Connect:

multiplicity ≤ 10000,

period ≥ 1000ms,

props.host ∈ {"10.0.0.5:443","10.0.0.8:80"}

}

}

// ...

func main() -> unit [Pentest] {

for (i = 0; i < 10000; i = i + 1) {

probe("10.0.0.5:443");

sleep(50); // sleep for 50ms

}

}

The program above will not be type checked as its delay between connections is less than 1000ms, which may lead to a DoS attack or flooding that is out of scope.

We built a programming language based on this idea. Pentesting actions are written as code. The type system encodes the scope of the engagement, which operations are permitted, and what effects on the environment are allowed. When the code compiles, all of this is checked. If any action violates the constraints, compilation fails. The action never executes.

Representing pentesting as a formal language has several advantages beyond AI safety.

- The entire pentest can be captured as code. A project can be saved and re-executed for retesting after remediation, without having to manually repeat the process or rely on the AI to reproduce the same steps.

- Each step of the engagement is documented and reproducible. The sequence of actions, the targets examined, the techniques applied—all of it is recorded in the program itself, providing a clear audit trail.

- Strategy becomes explicit. Rather than relying on implicit methodology encoded in prompts, pentesting strategy can be formulated and executed as code. This enables more systematic thinking about approach and coverage.

- Scenarios can be reused across projects. Common testing patterns can be abstracted into reusable modules, improving efficiency and consistency.

100% Safe Vibe Hacking

The most significant application, however, is enabling AI-assisted pentesting with formal safety guarantees.

The main limitation preventing broader use of AI in pentesting has always been unpredictability. An agent generating arbitrary shell commands could do anything—including actions that violate scope, damage systems, or expose sensitive data. Prompt-based constraints provide guidance but not guarantees.

By training models to generate code in our language instead of shell commands, the type system acts as a formal barrier against unsafe actions. The type system models the permitted operations and their effects. Operations that would violate scope or authorization constraints are rejected at compile time. The AI cannot "hallucinate" disallowed actions into existence—they will not pass type checking, regardless of what the model intended to generate.

This separation is important: the AI handles strategy, methodology, and adaptation to what it discovers. The type system handles safety. The model operates freely within the bounds defined by the types, but cannot step outside them. This is not a probabilistic guardrail that works most of the time. It is a formal constraint enforced by the compiler.

AI-Coders as Basis for AI Pentesters

AI has become quite capable at generating code in well-defined languages. The industry has invested heavily in this capability through tools like Cursor, Copilot, and Claude's coding abilities. By designing a language specifically for pentesting with the right type-level constraints, we can leverage this capability while maintaining formal guarantees about what the generated code can and cannot do.

There are additional architectural benefits. The AI generates code in the cloud, but the code itself is just text—logic and methodology. The interpreter that executes the code can run anywhere: in our infrastructure, on local machines, or inside a client's network. Findings and sensitive data stay wherever the interpreter runs. For environments where data cannot leave the network, the interpreter is deployed inside that infrastructure.

The formal foundation for this approach comes from research we published on type properties—a mechanism for attaching information to values that propagates through the type system and is resolved at compile time. For those interested in the theoretical underpinnings, the paper is available at akhmedkhodjaev.com/properties.pdf.

The broader point is that encoding constraints in a type system rather than in prompts may be a useful pattern for AI agents operating in high-stakes domains. Prompts communicate intent, but types enforce invariants. For domains where certain failures are unacceptable—not merely unlikely but truly prohibited—this distinction matters.

We hope this approach is useful to others facing similar problems.